Federal Court of Australia

Torrens University Australia Limited v Fair Work Ombudsman [2025] FCA 634

File number(s): | NSD 490 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | HALLEY J |

Date of judgment: | 16 June 2025 |

Catchwords: | INDUSTRIAL LAW – review of compliance notice issued pursuant to s 716(2) of Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) – interpretation of Higher Education Industry – Academic Staff – Award 2010 and Higher Education Industry – Academic Staff – Award 2020 (Awards) – construction of “associated working time” in hourly payment rates for lecturing by casual academics in Awards – where associated working time not limited to assessments confined to delivery of single lectures – where compliance notice issued by Fair Work Ombudsman incorrectly construed “associated working time” in Awards –compliance notice cancelled |

Legislation: | Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) ss 3, 716, 717 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) ss 21, 22 |

Cases cited: | Amcor Limited v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2005) 222 CLR 241; [2005] HCA 10 Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (Nine Brisbane Sites Appeal) (2019) 269 FCR 262; [2019] FCAFC 59 Print P0289 [1997] AIRC 301 Re 4 yearly review of modern awards – Education group [2018] FWCFB 1087 Re 4 yearly review of modern awards – Part-time employment and Casual employment (2018) 282 IR 135; [2018] FWCFB 4695 Re 4 yearly review of modern awards — Part-time employment and Casual employment (2018) 282 IR 234; [2018] FWCFB 5846 Re Annual Wage Review 2018-19 (2019) 289 IR 316; [2019] FWCFB 3500 Workpac Pty Ltd v Skene (2018) 264 FCR 536; [2018] FCAFC 131 |

Division: | Fair Work Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Employment and Industrial Relations |

Number of paragraphs: | 50 |

Date of hearing: | 26 May 2025 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr J Bourke KC and Mr K Brotherson |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Clayton Utz |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Ms V Brigden and Mr L Meagher |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Australian Government Solicitor |

ORDERS

NSD 490 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | TORRENS UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA LIMITED Applicant | |

AND: | FAIR WORK OMBUDSMAN Respondent | |

order made by: | HALLEY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 16 June 2025 |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

A. The Applicant has not contravened cl 18.2 of the Higher Education Industry – Academic Staff – Award 2010 (2010 Award) and cl 16.4 of the Higher Education Industry – Academic Staff – Award 2020 (2020 Award), as alleged in the compliance notice dated 19 March 2024 (Compliance Notice).

B. The Compliance Notice is founded on an incorrect construction of the 2010 Award and the 2020 Award and accordingly is bad at law.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Compliance Notice is cancelled pursuant to s 717(3) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

HALLEY J:

A. Introduction

1 The issue that arises for determination in this proceeding is the proper construction of the phrase “associated working time” in two industrial awards. The two awards are the Higher Education Industry – Academic Staff – Award 2010 (2010 Award) and the Higher Education Industry – Academic Staff – Award 2020 (2020 Award). The phrase as it appears in cl 18.2 of the 2010 Award and cl 16.4 of the 2020 Award has not been the subject of any decision of a Court or conclusive determination by the Fair Work Commission (FWC).

2 Employees of the applicant, Torrens University Australia Limited (Torrens), have been covered by both the 2010 Award and the 2020 Award (together, the Awards).

3 On 19 March 2024, a Fair Work Inspector (FWI) employed by the respondent (FWO), issued Torrens a compliance notice under s 716(2) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act). It was alleged in the compliance notice that Torrens had contravened cl 18.2 of the 2010 Award in the period between 7 May 2018 and 17 April 2020, and cl 16.4(a) of the 2020 Award in the period between 18 April 2020 and 18 March 2024, by failing to pay Ms Sophie Lucas, an academic lecturer engaged by Torrens on a casual basis, the marking rate for performing certain marking duties (Compliance Notice). The Compliance Notice was issued to Torrens under a covering letter from the FWO also dated 19 March 2024 (Compliance Letter).

4 Torrens seeks a review of the Compliance Notice pursuant to s 717(1)(a) of the FW Act on the ground that it has not committed the contraventions set out in the Compliance Notice. It also seeks various declarations, and that the Compliance Notice be cancelled pursuant to s 717(3) of the FW Act and/or s 21 and s 22 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

5 Torrens relied on an affidavit from Associate Professor Robyn Latimer OAM and the FWO relied on affidavits from Ms Lucas and Nicholas Lewis. None of the evidence given by them was the subject of any material dispute, and none was required for cross examination.

6 For the following reasons, I have concluded that upon a proper construction of the words “associated working time” in the Awards, Torrens has not committed the contraventions alleged in the Compliance Notice.

B. Background

7 Ms Lucas was employed by Torrens pursuant to a letter of appointment dated 15 May 2017 as an academic lecturer on a casual basis in its Design Faculty to teach design related subjects. The letter of appointment confirmed that she was employed on a casual basis and the then 2010 Award covered her employment.

8 Ms Lucas’ role involved preparing for and conducting lectures, marking assessments for students in the subjects she taught, and being available to provide support for students she taught. Torrens paid Ms Lucas the casual basic lecture rate set out in the Awards. Torrens did not pay Ms Lucas a separate amount for time that she spent marking, other than in limited circumstances such as where a student submitted work late, or where she marked the work of students she did not teach.

9 It was common ground that the assessments marked by Ms Lucas related to the subjects that she taught as a whole, not to individual lectures.

10 The Compliance Letter included the following explanation of the basis on which the FWO had formed a reasonable belief, as required by s 716(1)(b) of the FW Act, that Torrens had contravened the Awards:

In relation to Ms Lucas and marking activities, Torrens University appears to hold a view that the lecturing rate under the Award entitles casual academics to a fixed block payment for each lecture they deliver and “associated working time” includes all general marking activities, but may exclude “non-standard marking” as defined by the university as, “significant post grad marking, large class size, bespoke project marking, marking for a class where the individual didn’t teach it, or post graduate research submissions”.

Ms Lucas advised when marking assessments of her students in a trimester and during the week immediately after the trimester ended (the Week 13), Torrens University considered the hours of work as part of “associated working time” and only allowed for the “associated working time” allotted for each lecture delivery for all associated activities.

Ms Lucas described, for example, when marking certain assessments testing her student’s consolidation of knowledge on a range of topics covered in various lectures delivered across the trimester (e.g. a mid-trimester assessment or final assessment), she did not receive any extra pay in addition to the casual hourly lecturing rates paid to her.

We have considered evidence from a range of sources, and by taking a plain language interpretation of the Award, the FWO views “associated working time” as needing to be directly related to the delivery of a particular lecture or tutorial.

It is FWO’s view that when marking is undertaken by Ms Lucas of her students work in a given trimester including the Week 13, like the examples above, this is not considered “associated working time” because it is not directly associated with the delivery of a particular lecture or tutorial, it therefore must be paid at the applicable marking rate set out in the Award.

I hold a reasonable belief that, between 7 May 2018 and 18 March 2024, Ms Lucas performed marking duties on the assessments of her students which were not associated with the delivery of a particular lecture and was not paid at the applicable marking rate set out in clause 18.2 of the 2010 Award and 16.4 (a) of the 2020 Award.

11 Clause 16.4 of the 2020 Award relevantly provides that casual academics are to be paid the following minimum rates, inclusive of a casual loading:

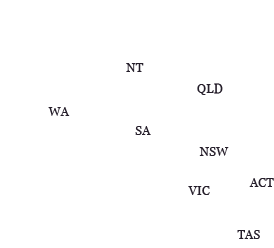

Casual hourly rate (including casual loading) | |

$ | |

Lecturing | |

Basic lecture (1 hour of delivery and 2 hours associated working time) | 160.48 |

Developed lecture (1 hour of delivery and 3 hours associated working time) | 214.02 |

Specialised lecture (1 hour of delivery and 4 hours associated working time) | 267.50 |

Repeat lecture (1 hour of delivery and 1 hour associated working time) | 106.97 |

Tutoring | |

Tutorial (1 hour of delivery and 2 hours associated working time) | 125.22 |

Repeat tutorial (1 hour of delivery and 1 hour associated working time) | 83.46 |

Tutorial (1 hour of delivery and 2 hours associated working time) (where academic holds a relevant doctoral qualification) | 142.13 |

Repeat tutorial (1 hour of delivery and 1 hour associated working time) (where academic holds a relevant doctoral qualification) | 94.70 |

… | |

Marking rate | |

Standard marking | 41.71 |

Standard marking (where academic holds a relevant doctoral qualification) | 47.37 |

Marking as a supervising examiner, or marking requiring a significant exercise of academic judgment appropriate to an academic at level B status | 53.49 |

Other required academic activity | |

If academic does not hold a relevant doctoral qualification or perform full subject coordination duties | 41.71 |

If academic holds a relevant doctoral qualification or performs full subject coordination duties | 47.37 |

12 The text, but not the rates, in cl 18.2 of the 2010 Award was in materially the same terms as cl 16.4 of the 2020 Award. The term “associated working time” where it appears in cl 16.4 of the 2020 Award and cl 18.2 of the 2010 Award is not defined in either of the Awards.

13 I note that the Full Bench of the FWC in Re 4 yearly review of modern awards – Education group [2018] FWCFB 1087 considered a submission by the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) that a definition of “associated working time” and other terms be included in the casual academic rates in the 2010 Award. The Full Bench stated:

[318] In its closing submissions, the NTEU indicated that some aspects of its claim had been addressed in the exposure draft process. Against that background, in relation to (i) above the NTEU indicated that it did not pursue any further changes than those already agreed during the exposure draft process. In respect of (ii), the NTEU maintained that in the absence of any definitions, the modern award failed to provide a fair safety net of wages. In support of its revised claim, the NTEU submitted that the rates of pay for lecturing and tutoring and the concept of associated working time for these and several other categories of casual academic work were key elements of the structure of the casual rates of pay in the modern award, adding that it was fundamental to a fair safety net the employers and employees to be able to determine which rates of pay attached to which work. The NTEU further highlighted that the pre reform regulation of these rates was characterised by clear statements limiting the circumstances in which different rates applied and that the modern award failed to do this.

[319] Specifically, the NTEU proposed the inclusion of the following definitions in either a new clause 9.4(c) [clause 9.4 of the exposure draft of the Academic Staff Award deals with rates of pay for casual employees] or as additions to the list of definitions at Schedule E to the Academic Staff Award.

…

(d) “associated working time” means time providing duties directly associated with the hour of delivery, being duties in the nature of preparation and reasonably contemporaneous marking and student consultation.

[320] Beyond this, the NTEU contended that defining the terminology used in the casual rates of pay table was clearly a term that may be included in a modern award as it either directly regulated rates of pay or was incidental to that regulation and essential for the Academic Staff Award to operate in a practical way. Further, inclusion of the definitions not only contributed to the establishment of a fair and relevant minimum safety net by ensuring clarity as to the operation of the Award terms but it also reduced the regulatory burden on employers and ensured the Award provisions were easy to understand.

(Emphasis in original.)

14 The Full Bench, however, was not persuaded that it was necessary to include the definition of “associated working time” and other definitions proposed by the NTEU. The Full Bench declined at [328] to vary the 2010 Award, in the terms sought by the NTEU, on the basis that:

[326] No evidence was led highlighting that the effective operation of the existing Award provision had been compromised in the absence of the NTEU’s proposed variation or that there was any uncertainty in the application of the award provision. Further, as the Go8 noted in its submissions, the wording proposed by the NTEU commonly appeared in enterprise agreements.

[327] Together these considerations do not support a finding that the minimum safety net is somehow deficient. While we note that the definitions were included in pre reform awards we are nevertheless not satisfied that their inclusion as proposed by the NTEU is necessary to achieve the modern awards objective, particularly as it appears that any issues arising from the absence of the definitions in the Award are being dealt with through enterprise bargaining.

C. Construction principles

15 Each of the Awards is a “modern award” made by the FWC under the FW Act to cover academic staff in the “higher education industry”.

16 As made plain in s 3(b) of the FW Act, modern awards, in combination with the National Employment Standards and national minimum wage orders, are intended to support the objective of the FW Act in “ensuring a guaranteed safety net of fair, relevant and enforceable minimum terms and conditions”.

17 The principles governing the interpretation of words in modern awards are well settled. The following fundamental propositions can be distilled from the summary of relevant principles provided by the Full Court in Workpac Pty Ltd v Skene (2018) 264 FCR 536; [2018] FCAFC 131 at [197] (Tracey, Bromberg and Rangiah JJ) in the context of interpreting enterprise agreements:

(a) the starting point is to construe the ordinary meaning of the words in context and read as a whole;

(b) the words must be construed in light of their industrial context and purpose, and not in a vacuum divorced from industrial realities; and

(c) the persons framing the words are likely to have a “practical bent of mind” and be more concerned with expressing concepts in a way likely to be understood in the relevant industry rather than with “legal niceties and jargon”, making it appropriate to adopt a purposive approach to interpretation of the words.

18 In adopting a purposive approach, the Court should construe an award in its industrial context and purpose: see Amcor Limited v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2005) 222 CLR 241; [2005] HCA 10 at [2] (Gleesson CJ and McHugh J); [96] (Kirby J). In construing an award in its industrial context and purpose, it should adopt an approach that contributes to a sensible industrial outcome: Amcor at [96] (Kirby J); Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (Nine Brisbane Sites Appeal) (2019) 269 FCR 262; [2019] FCAFC 59 at [5] (Allsop CJ).

D. Contentions of the parties

19 The central proposition advanced by the FWO in the Compliance Letter and then subsequently developed in submissions was that “associated working time” in the Awards under the heading “Lecturing”, at least with respect to marking activities, was limited to work undertaken that was directly related to the delivery of a particular lecture or tutorial (Direct Particular Lecture Test).

20 Torrens seeks a review of the Compliance Notice pursuant to s 717(1)(a) of the FW Act on the basis that the FWI could not reasonably have held the belief that the Direct Particular Lecture Test, as articulated in the Compliance Letter that accompanied the Compliance Notice, was sound in law and further, or in the alternative, a declaration that the test was bad at law or it had not otherwise contravened cl 18.2 of the 2010 Award or cl 16.4 of the 2020 Award and pursuant to s 717(3) of the FW Act and/or s 21 and s 22 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), the Compliance Notice should be cancelled.

21 Torrens submits that the lump sum payment for lecturing time in the Awards is based on notional assessments of time, rather than requiring specific monitoring and recording of actual time for “associated working time” for each lecture. It submits that the Direct Particular Lecture Test is divorced from the pedagogical realities of tertiary education that are directed at the building of knowledge and skills. It submits that contextually, marking should inevitably be included as part of “associated working time” and it would be both highly cumbersome and impractical to determine, let alone monitor, any construction that would limit “associated working time” to a specific lecture, rather than the delivery of the relevant subject.

22 The FWO submits that the natural and ordinary meaning of the words “associated working time” in their immediate context requires consideration of whether there is a requisite association between the delivery of a lecture and working time spent marking an assessment related to the subject as a whole. It submits that while words of connection take meaning from their context, it is apparent that any connection between the delivery of a lecture and the marking of an assessment referrable to a subject as a whole is highly tenuous and indirect. It submits that the natural and ordinary meaning of the words “standard marking” is that they apply to marking assessments.

23 Next the FWO submits that the words “associated working time” in their wider textual context do not support a construction that time spent marking assessments that relate to a subject as a whole falls within “associated working time” because (a) the language of “standard marking” suggests a distinction from “associated working time”, (b) the rates of pay under the heading “Lecturing” identify specific types of lectures as confined activities, (c) the higher rates of pay for more specialised lectures suggest payments for lecturing are intended principally to compensate for preparation time for lectures, (d) the number of hours allocated for “associated working time” do not vary depending on the size of the student cohort, and (e) the inclusion of rates of pay for “Other required academic activity” supports the view that “associated working time” was not intended to cover all work related to a particular subject performed by a casual academic.

24 Finally, the FWO submits that the construction of the words “associated working time” propounded by Torrens does not sit comfortably with the industrial context and purpose or the commercial context of the Awards. It submits that there is a great potential for unfairness and inconsistency of payment. It provides the following examples of unfairness that would flow from a construction that included within “associated marking time” all marking undertaken by a casual lecturer for students to whom they delivered lectures:

a. a casual academic staff member may be engaged to deliver one lecture as part of a subject only, with no assessment marking required, and another could be engaged to deliver multiple lectures as part of teaching a subject and marking of assessments in that subject, and the latter lecturer would not be paid more per lecture;

b. a casual academic staff member who delivers lectures marking a large number of assessments submitted by students taught by the academic in the subject would be paid the same as an academic staff member in the same position but with a smaller student cohort;

c. the marking rates would presumably apply to a casual academic staff member who did not lecture in the course being assessed, but only the lecturing rates would apply to marking performed by staff who did lecture in that course. It is unclear how Torrens says the Award can be interpreted to lead to this result; and

d. the estimated amount of associated working time is manifestly less than the time that would be expected to complete marking for at least many subjects, especially those with large student cohorts. This is borne out by Ms Lucas’ and Mr Lewis’ evidence as to the time taken by each of them to mark assessments.

E. Consideration

25 I do not accept that properly construed “associated working time” under the heading “Lecturing” in cl 16.4 of the 2020 Award and cl 18.2 of the 2010 Award is limited to work “directly related” to the delivery of a particular lecture. Rather, I am satisfied, for the following reasons, that the words “associated working time” in those clauses extend to all marking undertaken by a casual lecturer of assessments in subjects taught by that lecturer and that the “Marking rate” in those clauses applies in circumstances where a lecturer undertakes marking of assessments for subjects not taught by the lecturer.

26 First, and fundamentally, it was common ground and consistent with the evidence that the “working time” of a lecturer extended to marking assessments in subjects in which they lectured. Relatedly, it is significant that the NTEU in their submission to the Fair Work Commission referred to at [13] above, included “reasonably contemporaneous marking” within their proposed definition of “associated working time”. Hence the critical issue is the distinction between marking that falls within the concept of “associated working time” for lecturing and is thereby remunerated within the allowances for “Lecturing”, and marking that is remunerated at the hourly rates specified under the “Marking rate”.

27 Second, a requirement that working time can only be “associated” working time if it is “directly related” to a specific lecture finds no substantive textual support in the various provisions in cl 16.4 of the 2020 Award and cl 18.2 of the 2010 Award. The word “associated”, connoting a form of connection, is of significantly broader import than “directly related”. Textually, there is no reason to exclude working time in marking an assessment that concerns subject matter covered in two or more lectures from working time that was associated with a lecture for which remuneration was to be paid to the lecturer as part of the rates for “Lecturing”.

28 Confining marking to marking that fell within the Direct Particular Lecture Test would ignore the pedagogical realities of tertiary education. As Associate Professor Latimer explained:

Consistent with good pedagogy, matters taught earlier in the subject should not be simply left aside on the assumption that the student now understands those matters. Those matters need to be revisited and integrated in future lectures to ensure such learnings are properly grasped.

Hence, good educational practice requires the integration of each lecture with the educational subject matter of the entire subject, including for that matter, integrating the subject with the learnings that have come from any prerequisite subjects or courses. Such good practice teaching is known, in pedagogy, as “scaffolding”. This term reflects the fact that each lecture should be integrated with what had gone before and what is intended to be taught for the balance of the subject and course.

(Italics in original.)

29 Moreover, the FWO was not able to point to any coherent or principled basis that would provide a means by which marking would fall within “associated working time” or otherwise be remunerated at the “Marking rate”, other than to advance the proposition that only the marking of assessments that were limited to the delivery of individual lectures fell within “associated working time”.

30 In the course of oral submissions, counsel for the FWO advanced a theory that the “Marking rate” should be construed as applying to all assessments included in a course outline on the basis that the course outline had been prepared by someone other than the individual casual lecturers, such as Ms Lucas. The contention had not previously been advanced but more significantly, it impermissibly seeks to focus on the identity of the person who might have formulated the assessment rather than whether the marking being undertaken with respect to the assessment was “associated working time” to a lecture delivered by the casual academic. It is the connection between the lecture and the assessment being marked that is relevant. The question of who formulated the assessment and included it in the course outline cannot relevantly assist.

31 Third, the inclusion of a specific category for “standard marking” under cl 16.4 of the 2020 Award and cl 18.2 of the 2010 Award does not relevantly advance the construction issue. Textually the characterisation of marking as “standard” is used to distinguish it from marking undertaken by a “supervising examiner” or marking “requiring a significant exercise of academic judgment appropriate to an academic at level B status”. The requirement for the category is readily apparent in circumstances where the academic marking the assessment was not lecturing or tutoring in the subject and therefore would not otherwise receive any remuneration. Moreover, as explained below, the rate for “standard marking” was significantly lower than the rates for marking that fell within “associated working time”.

32 Fourth, and relatedly, any application of a “directly related” test that limits “associated working time” to work that is limited to a particular lecture cannot textually be limited to marking. It was common ground, and again consistent with the evidence before the Court, that “associated working time” included not only preparation and marking, but also consultation with students. It would be inherently problematic if lecturers were required to approach consultation with students on the basis that if the matters discussed were limited to the content of a discrete lecture it would be included in “associated working time” for lecturing but if the consultation was with respect to a topic or issue that had arisen in more than one lecture, then the lecturer could claim remuneration on an hourly basis at the rates specified in cl 16.4 of the 2020 Award and cl 18.2 of the 2010 Award for “Other required academic activity”.

33 Fifth, the examples of unfairness and inconsistency advanced by the FWO illustrate the inherent inflexibility in the practical application of an industrial award. It does appear to be incongruous and unfair that the remuneration for marking undertaken by a casual lecturer does not reflect or otherwise take into account the number of students taking a particular subject. This was an issue acknowledged by the Australian Industrial Relations Commission in Print P0289 [1997] AIRC 301 (Munro J, Watson DP and Frawley C) in which it addressed casual rates of pay for academic staff, including casual loadings and work descriptions in a number of former tertiary academic awards and in which it observed:

The current payment is organised around a set of assumptions and formulae about how much time is required to perform various functions. On the evidence, those assumptions and formulae underestimate significantly the amount of time worked in particular cases and therefore may not result in appropriate payment for some work regularly performed.

Student examination and essay marking, subject coordination, and student consultation are areas in which the evidence points to a significant demand on sessional casuals for unpaid work in excess of the level assumed in the calculation of the rate.

There is substantial evidence to support a conclusion that reasonable real preparation time required for many lectures is more than is allowed for by the current award standard rates. We accept that the amount of marking associated with a sessional lecture series will have increased proportionately to any increase in class sizes. Similarly, there is substantial evidence supportive of a conclusion that separate provision and payment for marking as a function separate from tutoring or lecturing would be more equitable than the existing system.

There is of necessity an arbitrary element in the attribution to the lecture rate of payment for one hour of contact and two hours of associated work. No adequate foundation is established for declaring another arbitrary attribution of three hours of associated work to one hour of contact time. The awards currently prescribe lecturer rates by reference to one of three “contact hour” rates for an initial lecture; the rate is selected by the employer. Those rates were arrived at by a calculation providing for one hour of lecture delivery at a rate linked to the midpoint of the lecturer scale in force in 1980, and two hours of associated duties on the first level, and for three and four hours of associated duties at the next two levels. Similar calculations underlay the tutor and demonstration rates built on a nexus with step 2 and step 5 of the then operative tutor pay scale.

(Footnotes omitted.)

34 As I explain at [5] above, the evidence as to the industrial context in which to construe the Awards in this proceeding was given by Associate Professor Latimer, Ms Lucas and Mr Lewis.

35 Associate Professor Latimer gave evidence, that I accept in the absence of any substantive challenge, or evidence to the contrary, that it was improbable that any assessment at Torrens would ever be limited to the delivery of a particular lecture or tutorial. As she explained, for pedagogy, “good assessment practice” is progressive and “should be focussed on assessing a student’s understanding of the course at that point in time, including possibly seeing whether the student has sufficient command of matters covered in any prerequisite subjects”.

36 Both Ms Lucas and Mr Lewis gave evidence, consistently with the evidence given by Associate Professor Latimer, of the progressive forms of assessment that they employed. The only exception to this approach to assessment was an example provided by Mr Lewis of stand-alone work tasks that he sets in lectures for students to work on in their own time, but that do not form part of their subject grade.

37 Ms Lucas gave evidence that in some circumstances, she was separately paid for marking assessments at the marking rate in the Awards. The examples that she gave were limited to where she was marking the work of students that she did not teach or for assessments submitted late by her students when an extension had been granted.

38 Ms Lucas otherwise gave evidence that (a) she taught between two and seven subjects in each trimester of 12 weeks, (b) each subject would typically have one 3 hour lecture each week and three or four assessments each trimester, and (c) on average she would have 15 students in each bachelor subject. On this basis, assuming the lower end of the range she would have had 90 assessments to mark each trimester (2 subjects x 3 assessments x 15 students). On the other hand, at the higher end of the range she would have had 420 assessments to mark each trimester (7 subjects x 4 assessments x 15 students).

39 Next, Ms Lucas gave evidence that until the first half of 2020, it typically took her between 35 to 45 minutes to mark assessments for each student and since then she has used the Snagit screen recording marking tool to mark some assessments. She states that it takes her typically 20 minutes to mark each individual assessment using the Snagit tool. Leaving to one side any use of the Snagit tool from 2020, the evidence given by Ms Lucas of her average marking time would then lead to a total marking commitment for each trimester during the relevant period at the lower end of the range of hours (90 assessments x 45 minutes = 4,050 minutes, that is 67.5 hours) and at the higher end of the range of hours (420 assessments x 45 minutes = 18,900 minutes, that is 315 hours).

40 Mr Lewis gave evidence that on average he has 20 to 25 students at the commencement of each of the two units that he teaches at Torrens, falling to 15 to 20 students by the end of each unit due to withdrawals. He gave evidence that it takes him on average 10 to 15 minutes to mark each week 4 assessment, 15 to 20 minutes to mark each week 8 assessment and approximately 20 minutes to mark each week 12 assessment.

41 The evidence given by Ms Lucas and Mr Lewis might suggest that it was not uncommon for their marking commitments to exceed significantly the notional allowances for preparation, marking and student consultation in the remuneration provided for “associated working time” for lecturing. That evidence, however, is inherently problematic when the implications of that evidence are exposed, in particular, when the remuneration that might be payable if marking was to be separately remunerated to lecturing time is compared with the rates for full-time academics given casual academic hourly rates have been determined by reference to those rates.

42 For the purposes of the following calculations, I have referred to the specific clauses in, and used the figures from, the version of the 2010 Award, as varied by Re 4 yearly review of modern awards – Part-time employment and Casual employment (2018) 282 IR 135; [2018] FWCFB 4695, Re 4 yearly review of modern awards — Part-time employment and Casual employment (2018) 282 IR 234; [2018] FWCFB 5846 and Re Annual Wage Review 2018-19 (2019) 289 IR 316; [2019] FWCFB 3500, that was current in 2019.

43 Clause 13.1 provided that casual employees were to be paid at an hourly rate that was 1/38th of the weekly base rate derived from the relevant classification plus a loading of 25% referrable to award-based benefits for which casual employees were not eligible.

44 Clause 13.3 provided that the base rates applicable for “lecturing” and the “higher marking rate” were to be determined by reference to the second step of the full-time Level B scale, and for all other duties, other than full-time subject co-ordination or where the employee had a relevant doctoral qualification, the base rate applicable was to be determined by reference to the second step of the full-time Level A scale. Hence, “standard marking” was to be calculated by reference to the second step of the full-time Level A scale.

45 The annual salaries for full-time academic staff were specified in cl 18.1 of the 2010 Award. The difference between the second step of the full-time Level B scale (an annual salary of $70,879) and the second step of the full-time Level A scale (an annual salary of $55,297) was significant. This difference was reflected in cl 18.2 in which the lecturing rate for a basic lecture of $134.08 (1 hour of delivery and 2 hours of associated working time) represented an hourly rate of $44.69 compared with an hourly rate of $34.84 for standard marking.

46 I turn now to consider the implications of these calculations on the remuneration that a casual academic would receive under the 2010 Award if all marking was to be paid under the standard marking rate. Applying the pre-2020 marking assessment time of Ms Lucas of between 35 to 45 minutes, assuming an approximate mid-point of five subjects a trimester and noting that Ms Lucas gave evidence that in the period prior to 2024 final marking was undertaken in a notional week 13 in which there were no lectures, the total remuneration received by Ms Lucas for the 13 weeks of the trimester would be as follows:

(a) lecturing remuneration of $24,134.40 (5 subjects x 3 hours x $134.08 x 12 weeks); and

(b) standard marking remuneration of between $4,546.62 (5 subjects x 3 assessments x 15 students x 0.58 hours (35 minutes) x $34.84) and $7,839.00 (5 subjects x 4 assessments x 15 students x 0.75 hours (45 minutes) x $34.84).

47 Hence on the basis of these calculations that rely on an approximate mid-point of the evidence given by Ms Lucas, she would have been paid between $28,681.02 and $31,973.40 each trimester if she had been remunerated for marking under the standard marking rate under the 2010 Award. This remuneration is significantly higher than the remuneration a full-time lecturer would receive for the same 13-week period, even after allowing for the 25% loading for casual staff. The annual salary for a full-time equivalent second step Level B academic under the 2010 Award was $70,879. This translates to a salary for a 13-week period of $17,719.75 ($70,879 divided by 4 (that is, 52 weeks divided by 13 weeks)), which then increases to $22,149.69 if a 25% loading is added to enable the rate to be more fairly compared with a casual rate. It is telling that the comparative grossed up figure that a permanent equivalent academic lecturer would have been paid for 13 weeks is materially lower than the remuneration that Ms Lucas would have received for teaching five subjects even without any payment to the casual lecturer for “standard marking”.

48 Sixth, and finally, I am satisfied that consistently with established principles of construing modern awards, the words “associated working time” extend to the marking by lecturers of assessments undertaken by their students where the assessment is directed at the content of lectures that they have given to their students. It focusses attention on the words actually used in the Awards, and gives effect to their objective, expressed intention gathered from those words in light of their context and purpose. Such a construction would provide a “sensible industrial outcome” given that at least some marking is generally accepted to fall within associated working time and assessments are rarely, if ever on the evidence before me, confined to single lectures. The definition that had been proposed by the NTEU to the Fair Work Commission of “reasonably contemporaneous marking” does not materially advance the position. It seeks to confine the breadth of “associated” to a temporal element and to a temporal element that is itself inherently qualitative and uncertain.

49 Given my conclusion that the Compliance Notice is founded on an incorrect construction of the Awards and is accordingly bad at law, I am also satisfied that the FWI could not reasonably have held the belief pursuant to s 717(1)(a) that the Direct Particular Lecture Test was sound at law.

F. Disposition

50 For the foregoing reasons, declarations should be made that the Compliance Notice is founded on an incorrect construction of the Awards and is accordingly bad at law. Further, an order is to be made that the Compliance Notice be cancelled pursuant to s 717(3) of the FW Act.

I certify that the preceding fifty (50) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Halley. |

Associate:

Dated: 16 June 2025